I got a special treat the other day. The chief of our resource division decided that I should see another part of the park so he took me with him to see a small chunk of what his job is about. This was very pleasing to me as it gave me a chance to see Warner Valley, an area that holds many of the thermal features, some of the more unique aspects of Lassen Volcanic National Park.

It is also an area with a unique historic feature: Drakesbad. Drakesbad is named for a guy (Drake) who put a mining claim on the hot springs back before the park existed. He sold it to a doctor (Sifford) who built a bath (Bath=Bad in German) house with the usual claims of medicinal properties. The bath house grew into a ranch set up with a dining lodge and several cabins. The area was an escape for wealthy folks living in the Sacramento Valley. The Siffords, who incidentally helped get the national park created, eventually deeded the area over to Lassen in the 1970s where it has become an interesting tangle of competing interests.

The ranch with its buildings are old, a touch over a hundred years. This means they are classified as historic structures which thus deserve special protection. Their use as an escape/recreational venue is also a special cultural resource. The ranch is ran by a concessionaire that charges visitors for use of the facilities and pays the park a certain sum to help pay for maintenance of the buildings (which doesn’t actually pay for the cost meaning the park operates the ranch at a loss). The hot springs are a natural resource of obvious value plus there is a fen in the valley that it rare for the area, particularly because it is fairly acidic (from the hot springs) making it sort of similar to a bog. Also, the wilderness area begins a few miles up the valley covering the largest concentration of hot springs: the Devil’s Kitchen. Oh, also the Pacific Crest Trail passes right by the ranch, with hikers sometimes stopping to pick up packages. The park has legal mandate to manage for all of those uses. As an extra complicating factor the ranch has several wealthy users who have long family histories of visiting the area since before it was gifted to the park. These benefactors hold prominent positions on the Lassen Volcanic Foundation, a nonprofit that collects funds to pay for special projects in the park.

On this particular visit we were following a class from the Red Bluff High School. Some teachers down there had a great idea to partner with NASA scientists and study the biochemistry of the hot springs as a stand in for conditions on Mars. So for 9 years they have been visiting the thermal features of the park to identify the cyanobacteria as they vary from hot spring to hot spring based on acidity and temperature and so forth. It turns out Lassen has chemotrophs which use hydrogen sulfide as an electron acceptor instead of oxygen. Very cool and unusual. The students spent the night in the campground then spent the day dividing into groups and sampling the chemistry and bacterial mats of the various hot springs scattered up and down Warner Valley. They take the biological samples back to the school and attempt to raise them under laboratory conditions.

The NASA scientists (who are part of the rover Teams for Curiosity/Opportunity and Spirit) discovered that the manager at the Drakesbad Ranch was cleaning the bacterial mats out of the hot springs because the algae was clogging the filter to the pool. He figured he could take a broom to the stream channels, sweep out the algae, and increase the flow of water into the hot spring fed pool. The NASA guys got upset because their algae/bacterial mats were no longer under natural successional conditions as the mat was essentially restarting every 2 weeks when the channel was scrubbed. So the pool guy stopped cleaning the channel and the filter started getting clogged up and reducing the flow so the pool was colder and algae started getting into the swimming pool making it a less attractive green color. Jason, our resource chief, had the task of talking to the scientists and the concessionaires to find some happy median between the competing resources.

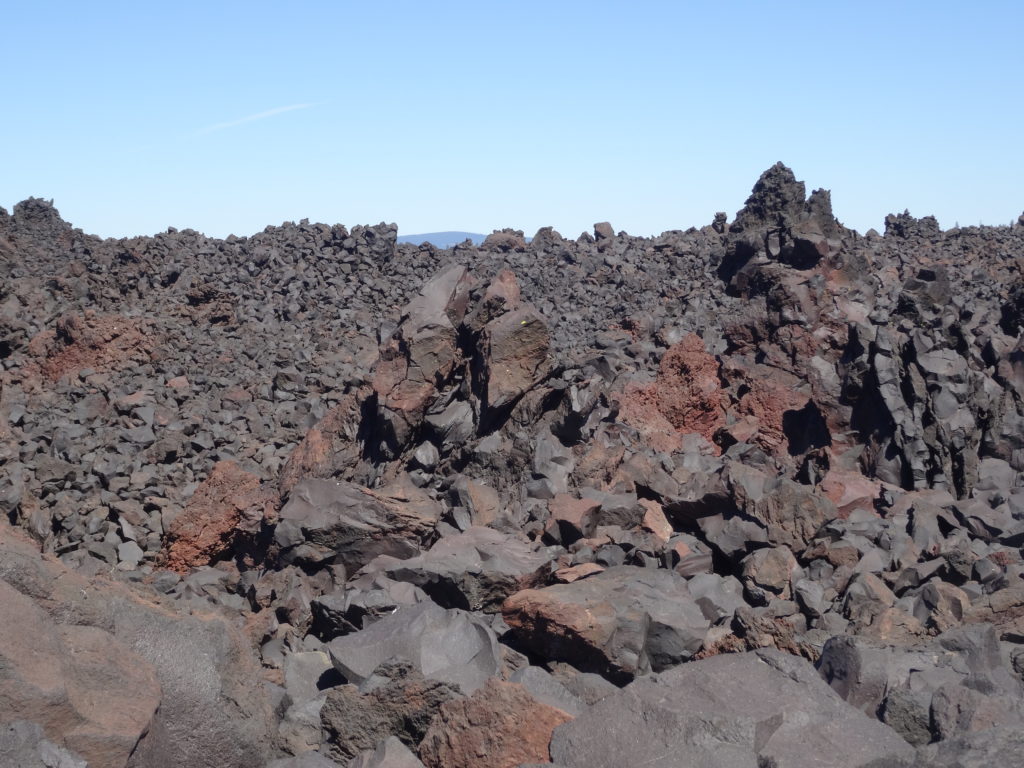

Devil’s Kitchen. A mess of geothermal features in the middle of a wilderness area. The bridge is illegal, but it crosses a small creek of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria at a measured pH of 1.3. You should not step it that.

At the same time we walked up to the Devil’s Kitchen where a number of visitors have requested the construction of a bridge over a small creek crossing. This is inside the wilderness area where the law mandates the area remain free from development and the signs of humanity. However the thermal feature is covered in bridges and railings, obvious signs of the manipulations of society and necessary to protect the frequently-visited and fragile thermal features. So, do we add a bridge (where most visitors have no problem crossing via a few rocks) in spite of the wilderness designation or do we leave the stream untouched in spite of the frequent visitors and slight hardship to a small number of older visitors?

National parks belong to all of us. That is why they are a fantastic symbol of democracy. But because we are such a diverse people providing for everyone’s use often leads to conflict. With full awareness of our own biases we must carefully explore options to benefit everyone, from the Martian NASA scientist to the Drakesbad pool boy.

Recent Comments